A Fermented Green Coffee That Tastes Like Cherries

It tastes nothing like the coffee you had this morning.

Welcome new Weird Drinkers! And thank you to all who have shared these stories.

Coffee is the one of the world’s most traded commodities. It’s everywhere. But availability doesn’t mean predictability, especially for a drink born in a Brooklyn neighborhood called Greenpoint.

Fermentation is truly a wonder of the natural world. It’s one of those foodie functions that is at once both ordinary and freaky—the chemical process of living yeast and bacteria frantically breaking down one substance into another. A form of digestion happening outside the guts.

Fermentation is vital to many of the drinks humans regularly consume, from beer and wine to hot chocolate and tea. It’s the kind of near-alchemy Weird Drinkers love to celebrate.

It may come as no surprise, then, that coffee is also a product of fermentation. Known as coffee cherry fermentation, coffee processors employ the technique to remove a thin layer of plant tissue from the unroasted coffee seed, or bean, prior to drying.

But what happens when fermentation, normally a utilitarian step in processing coffee, goes haywire? What happens when green coffee beans are intentionally subjected to multiple fermentations?

In that case, Weird Drinkers are treated to a genre-defying, milky-green, probiotic, effervescent caffeinated concoction that bridges the temporal and geographic spaces between fruit and beverage. In other words, a “mostly unknown expression of coffee” is born.

Before pouring a glass of this Frankensteinian elixir, however, it’s worth having a look at how fermentation is typically harnessed in coffee production

Coffee the beverage comes from coffee trees that produce a fruit known as coffee cherries that (usually) contain two coffee seeds. The red fruit has a fresh, slightly sweet, slightly tart flavor. The fruit is delicious enough to have enticed the first coffee “drinkers” to pluck the edible cherries from trees. Lacking the equipment for a nice pour over, they opted for a mandible brew: chewing the raw seeds and swallowing the mixture.

A whole coffee cherry, a thin layer of plant tissue (mucilage) and beans (courtesy Jeremiah Borrego)

As coffee became more widely consumed, coffee growers, processors and roasters developed new techniques for preparing a cup of joe. Since the 13th century, roasting coffee, as a method of preservation and flavor transformation, has become quite widespread.

Coffee beverages begin with harvested coffee cherries. After harvest, processors let naturally occurring yeasts and bacteria break down and separate the fruit portion of the coffee from the seed portion. After this fermentation, processors clean, dry, hull, grade and ship green, or unroasted, coffee to coffee roasters.

Roasters, in turn, expose coffee beans to heat and produce the finished ingredient for the black caffeinated beverage commonly recognized as coffee.

So long, mandible brews.

Lately, however, green coffee has been making a comeback. Instead of proceeding straight to the furnace after receiving green coffee beans, some have begun the coffee beverage preparation without roasting. Four years ago there were reports that green coffee, a bitter drink with potent quantities of caffeine, might take off with consumers. TV personality Dr. Mehmet Oz ran with a theory that green coffee extract could aid in weight loss.

But even the most diehard coffee lovers tend to shun the stuff. One taste test, conducted by Sandra Elisa Loofbourow, the Tasting Room Director at an Oakland-based coffee education center called The Crown, concluded that green coffee extract tastes like “a mix between soggy burlap, old peas and herby chamomile.”

“That people had the determination to get caffeinated before roasting became common practice is frankly impressive,” she added.

It makes sense. Why drink green coffee when black coffee is so much tastier?

Three years ago, experiments with coffee beans led Jeremiah Borrego, founder of Olas Coffee, to develop a unique double-fermented sparkling green coffee beverage that reconnects coffee drinkers with coffee cherries—and might even have some extra health benefits.

Borrego’s experiment began with a series of challenges.

He wanted to pay coffee farmers a specialty price for their harvest, even if they weren’t producing a speciality grade of coffee. That would mean his finished product had to stand out and command a price worthy of the process.

He wanted to explore a wider palette of coffee varietals, using “flavor notes in defective roasts [that were] not inherently distasteful,” as he told one publication.

Most importantly, the coffee entrepreneur wanted to make something new.

To do so, he turned to microbes, malting and time. Instead of controlling the temperature of a roaster, he tinkered with the environmental conditions of a vat of green coffee beans. Instead of churning out black and brittle roasted beans, he soaked them while they were still green and soft, reanimating the coffee seeds until they were beginning to sprout, then dousing the extract with a microbial stew of yeast and bacteria. He added sugar, to help catalyze a mix of anaerobic and aerobic fermentation, eventually zeroing in on a fermentation period of seven to ten days, with a second fermentation after bottling.

A green coffee bean beginning to sprout after soaking in water (courtesy Jeremiah Borrego)

He called the finished product Virbuna. It’s a milky, fruity and acidic greenish-white beverage with light effervescence, notes of grass and a hint of spiciness. It’s caffeinated. The dryness of the beverage, almost like a cucumber saison, comes from the green coffee seeds. Beneath it all lingers the coffee cherry, arguably the closest most coffee drinkers will ever come to tasting one plucked straight from the tree.

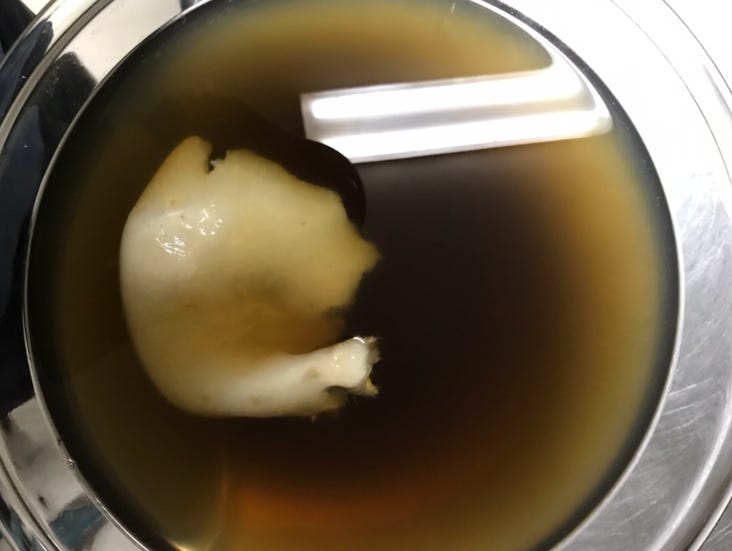

Green coffee after it’s been soaked and prepared for fermentation (courtesy Jeremiah Borrego)

It’s even possible Borrego’s recipe is healthier than standard coffee.

A recent study on green coffee beans and nutrition found that green coffee beans, fermented with a yeast and water combination for 24 hours, resulted in fortification with “significantly increas[ed] antioxidant activity,” even after rinsing the beans three times and roasting them.

Yeast fermentation increased antioxidant activity “significantly” and increased the number of flavonoids in the coffee, according to the paper, published in the Journal of Food Quality. The impact fermentation had on antioxidant levels was similar to fermentations of ginseng, garlic, tea and soy.

There are significant differences, however, between the methodologies used by Borrego and the researchers. Borrego adds microbes to a brewed extract of green coffee, not the beans. The researchers added yeast directly to the bean and water mixture. Furthermore, the study did not look at the effects of fermentation on unroasted green coffee beverages served directly to test subjects. The study’s authors did not respond to a request for comment on any similarities or differences between a green and standard preparation of coffee.

Adding the microbial culture to the green coffee mixture (courtesy Jeremiah Borrego)

But even without scientific proof, the flavor of Virbuna is a proxy for healthiness, said Borrego. “To me the fermentation process is like nature signaling what, and when, a beverage is good for human consumption,” he said. “It’s a way for humans to reconnect with nature and natural products.”

“The culture is really friendly to the human digestive system,” he added. “When the culture is happy, that’s the signal to us: this is good for us.”

It’s early innings for this new fermented coffee-based beverage. Like roasting, fermenting the green beans preserves their qualities, allowing Virbuna to be aged. Year-old brewed coffee would rarely be described in glowing terms. But a year-old test batch of Virbuna “tastes like honey water,” Borrego said.

The fermentation process also allows for a mindboggling combination of microbial and environmental variables, on top of the standard control levers of coffee varietal, harvest year and terroir.

A bottle of Virbuna, in Brooklyn

“It’s a whole wide world in terms of fermentation,” he said. “There are truly just as many variations in fermentation as one could dream up, which makes it exciting.”

The drink is so different from the standard associations usually reserved for fermented or coffee-based drinks—kombucha, green coffee extract or even poorly-roasted coffee—that Borrego wants to see a new category for the drink. “It is different enough to warrant its own kind of designation,” he said.

While nothing replaces the experience of visiting a coffee farm to pick and eat ripe coffee cherries straight from the tree, it’s as close as one can get without being there, he added.

“It’s sort of the fresh state of coffee,” he said. “It’s a really interesting and mostly unknown expression of coffee.”