The Unlikely Firemilk Made by Animal Herders

Forget firewater: these parmesan cheese-flavored shots are made from milk and smell like wool (“but in a good way”).

Weird Drinkers love their unusual spirits (and there are plenty out there, like this natural blue gin or a booze produced from coconut flower nectar). Today’s potent beverage comes from the traditions of central Asia.

When it comes to unique distillates, shimiin arkhi is a true outlier. Sometimes called nermel, shimiin airag or saali-yin airagi, shimiin arkhi is a spirit distilled in Mongolia from fermented animal milk. Not only does it have a flavor unlike any other, but the raw materials that go into the stuff allow its animal-herding producers leeway denied most others.

Weighing in at 12-20% alcohol content, this...ahem....firemilk trades potency for flavor. It can be made from fermented cow, yak or camel milk, as well as Mongolia’s “gold medal drink,” a fermented horse milk beverage called airag. (Fresh mare’s milk is so sweet it has been compared to “cereal milk.”)

Those lactose building blocks mean this category-breaking weird drink has a distinctly cheesy taste.

“It definitely smelled like a liquor made from dairy,” said Shevan Wilkin, a postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany. A former bartender, she tried her first swig of shimiin arkhi in Ulaanbataar, Mongolia, while on an archaeological research trip.

“I was very interested,” she said. “When I sipped it, I could taste an aged cheese—kind of like a really nice, old parmesan. It doesn’t taste very strong, and was very easy and pretty smooth to drink.”

Another first-time shimiin arkhi taster was also impressed by the smoothness and dairy-like qualities of the drink. A cow milk version of the distillate tasted “a bit tangy and a bit ‘sheepy,’ like the smell of wool. But in a good way,” said Sarah Pederzani, a graduate student in archaeology at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

She described a strong alcohol taste, but said the drink wasn’t served as a shot; rather it was meant to be sipped.

Serving up some shimiin arkhi (courtesy Björn Reichhardt)

“It’s really the only alcohol that’s not made from plant materials,” explained Dr. Kirk French, an anthropology professor at Penn State University. He, too, found the taste unlike anything he’d tried before. “There are notes of earth and barn and hay,” he said, adding that he jumps at the opportunity to stump local distillers with a sample of the clear mystery liquor.

But that’s not the extent of shimiin arkhi’s surprises. Besides its attention-grabbing aroma and flavor, Mongolian herders who make the homemade hooch can more safely utilize an alcohol-strengthening technique that’s ordinarily fraught with danger.

Called freeze distillation, or “jacking,” Mongolians in search of something stronger than the initial 2% alcohol content of airag can use the extreme temperatures of the steppe to their advantage, making a sort of backdoor shimiin arkhi.

“The nomads of central Asia apparently applied ‘freezing-out’ to their alcoholic mare’s milk,” notes food writer Harold McGee in his book On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen.

How does this work? Distillation is the most common way of concentrating alcohol from a fermented liquid, but freezing also works. As an alcoholic beverage is frozen, the water will freeze before the alcohol. By freezing and removing the frozen parts of the beverage—then repeating the process—the alcoholic portion of the mixture is “jacked,” or concentrated. (This is how applejack gets its name.)

But the technique isn’t without its risks. Not only does buzz-inducing ethanol get concentrated, but trace amounts of dangerous substances can too. One of those is vegetable-derived methyl alcohol. Ingesting methyl alcohol, also called methanol or wood alcohol, can cause blindness and even death in severe cases.

While “jacking” airag into something resembling shimiin arkhi is technically feasible, during the high season of distillation, from July to October, it’s far more common to see Mongolians using a homemade system of distillation to produce their firemilk.

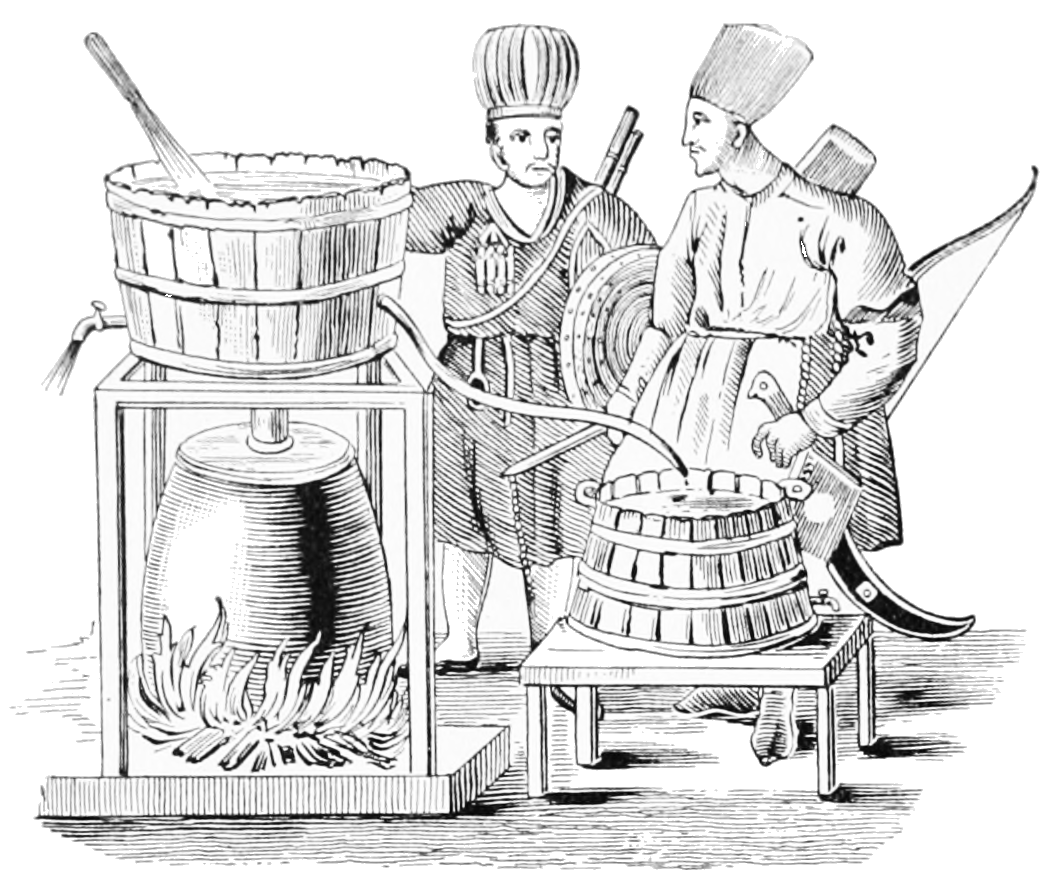

19th century engraving of firemilk distillation, from Appleton’s Popular Science Monthly

The process starts with heating a large pot of airag, said Björn Reichhardt, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany who has been studying dairy use in central Asia for Dairy Cultures.

When the liquid reaches a temperature between 120 and 140 degrees Fahrenheit, the distiller takes a large hollow cylinder, called a bürkheer, and places it edge-to-edge on top of the pot, like a sort of chimney. Over that goes a large cast iron bowl of cold water or milk, which acts as the condenser.

Rags are used to seal the joints in the still and a small pot placed under the curved bottom of the condenser, or a spout leading off to the side, is used to catch the concentrated alcoholic beverage. It takes around 40 to 50 liters of airag to produce 2 liters of shimiin arkhi.

A modern shimiin arkhi still. Note the heat source at the bottom, topped by the pan of airag, the barrel-like bürkheer and the pan condenser. Rags seal the joints. The concentrated alcohol comes out the side of the still (courtesy Dr. Jessica Hendy)

A double fermentation can boost the liquor, called arz at that point, to 30% alcohol content, according to the Khovsgol Dairy Project.

Either the first or second distillation could increase the risk of methanol poisoning if shimiin arkhi were derived from plant material, said Dr. French, who produced a video showing the process.

“If you distilled corn in this thing, you would definitely get methyl alcohol,” he said “It would be much more dangerous if you were using that type of process for plant material.”

But Mongolian distillers are saved that risk because of airag’s animal origins.

A shimiin arkhi still made of metal (courtesy Sarah Pederzani)

A colorful drink deserves colorful traditions. Shar tos, a type of yellow clarified butter, is added to shimiin arkhi and is believed to help deal with freezing cold temperatures, said Reichhardt. Drinking hot shimiin arkhi is said to help cure colds and a version of the liquor derived from cow’s milk will apparently cure hangovers.

Shimiin arkhi production is truly homegrown, and each set up has its flavors and aromas. Liquor made from fermented yak milk is fatty and more aromatic, noted Reichhardt. A bürkheer made from aspen wood produces liquor considered to be “particularly delicious” and healthier than one made from other materials. Some bürkheers are passed from generation to generation. Reichhardt saw one that was more than 100 years old.

Weird Drinkers looking for shimiin arkhi are best off booking a flight to Mongolian. Besides one personal stash from a visit to the country, no one seemed to know where it could be found outside of central Asia. Even in Mongolia, they said, there’s a better chance of finding this centuries-old parmesan-flavored firemilk in the countryside, rather than an urban marketplace.

For a drink as unusual as shimiin arkhi, undertaking an adventure to find it seems only appropriate.